Re-printed with permission by Justin Louis Pitcock

It is inevitable that a republic like ours will be altered by passing years and attitudes. It is supposed to be that way. The constitution left a hefty burden on the states and the Congress to answer the questions of the day. The law-making bodies that be, at both the federal and state level, have risen to the occasion many times. The bill of rights comes to mind. The Civil Rights Act and the Freedom of Information Act have their place in history as fruits of the legislature. But what happens when the Congress or the states get it wrong and why do we have so much trouble doing the right thing today?

We should know what happens when Congress gets it wrong. It happens often. “Getting it wrong” is what comes to most folk’s minds when they think of Congress today. It is a valid assumption. We do know. We can see the results of poorly written or enacted, even ill-intentioned regulation all around us. The Affordable Care Act is a hot topic in this vein. Signs indicate that it was written with political risk in mind rather than patient risk. The real tragedy is that it can be salvaged and the problem of an uninsured population more suitably addressed, but flame throwing political rhetoric is a growing obstacle to doing so.

Social security and other safety net programs were well intentioned and, on the whole, were well conceived. After many years passed without adjustments to funding or benefits, the topic now rages and divides one day and is tabled the next, when what seem to be more pressing topics arise. Meanwhile, the programs are on a known path to failure and ensuing crisis. It’s an opportune political football when nothing else is going on and a predicament we can simply put in our children’s lap when something else diverts the public gaze.

My point here is not as narrow as reforming specific legislation, though that is important. I want to talk about the structural pillars of this republic and the foundation on which they lie. Some of those pillars stand strong against the test of time and are as useful today as they were on the day President Washington was sworn in. The distribution of power between the three branches and the checks and balances in place because of that dynamic are central to honest government. Assignment of responsibility as the Commander in Chief, Head of State, and Head of Government entrusts a lot to one American, but has yielded efficient and effective results in times of crisis.

Other attributes of our constitutional foundations come under fire from time to time. The Electoral College received condemnation recently in 2000 and again in 2016. President Franklin Roosevelt gave reason for constitutionalizing the number of Supreme Court justices. Every 10 years, a new case is made for specificity in the arena of drawing congressional districts. These are but a few of the areas in which some repair has been done, but increasingly some of these pillars are eroding and losing their purpose of supporting the ideals on which this republic was founded.

“That unresolved issue almost cost us the union and did cost us almost a million American lives”

At this juncture, a long “ode to the constitution” is due but, to keep it short, it is sufficient to say that the United States Constitution is the single most important document written since the bible. Its formation is a beautiful amalgamation of careful study of the past, admiration and longing for human freedom, and painful compromise. What we were left with was far from perfect but, considering the environmental conditions leading up to its signing, the original constitution was the capstone to a truly remarkable achievement. Since then it’s been amended 27 times, contributing to the document’s strength.

It should be stated plainly, every time the subject of constitutional formation arises, that the issue of slavery casts a large dark shadow over the whole enterprise. Those who would discount the entire original document have a leg to stand on because of it. The obvious horror of slavery is not only a stain on that original beautiful amalgamation, but it was also an issue left unresolved in 1789. That unresolved issue almost cost us the union and did cost us almost a million American lives 70 years later on domestic battlefields from Gettysburg to Vicksburg. There are reasons and excuses for why it happened that way, but what matters is that the failure to do the right thing from the start put everything at risk. The lesson here to carry forward is that doing what is just, as soon as we know it to be so, is imperative – morally and practically.

That is the case now. There are several things we know about today that are prohibitive to a properly functioning American government. I’m not talking about hot-button partisan issues. The pro-life versus pro-choice debate is a strong partisan issue that is probably not going to be put to rest in my lifetime. The key to having these debates and making substantive progress in resolving any issue though, is the way in which they are conducted. To find out what is just, and to be able to act on it, passion must be balanced with reason. Self-interest must be balanced with empathy. Tradition should be honored, but not at the cost of preserving an oppressive culture. Our discourse today is at odds with these worthy goals and the most equipped entity able to change the tide is the individual American citizen.

“For good reason, our citizens have lost much of the faith in their leaders and institutions that they had in the early 20th century.”

A major problem with our discourse lies in our expectations. “Telling it like it is” is a stated desire by many voters when it comes to qualities they would like to see in their representation. People generally want to know how a leader “really feels.” The interpretation of this desire however, is almost the opposite of its literal meaning. “Telling it like it is” is accepted by many to mean “saying an opinion without regard to that opinion’s practicality of implementation or second order effects.”

In the past, a politician would state their position and then dance around tough questions about its implementation that would be politically damaging. This dance is what the term “politically correct” has come to mean and recently people’s irritation with such behavior has climaxed. This dance is understandably irritating to anyone trying to understand the stated position’s ramifications based on a single interview vice viewing the dance with well-read knowledge of the subject.

To illustrate, let’s take the issue of illegal immigration. Before the war on “political correctness” started, a politician might say their position is that the immigration laws of this nation must be enforced, but that there must be some provisions for children or families who’ve been here for a decade or a number of other possible circumstances. When asked about enforcing our immigration laws, the politician would attempt to evade the notion ICE agents would be “rounding up” immigrants for deportation. When asked about whether the provision for families who’ve been here for a decade, the politician would evade the notion that the provision is “amnesty” for immigrants who’ve broken the law by entering our country illegally. Someone watching an interview with any knowledge of the practically of the matter would generally be able to understand where the politician stands…”Amnesty for some?” Yes. “Round up of others?” Yes.

The contempt for the dance that is “political correctness” invites a different scenario. Today when a politician’s stated position is that the laws of this nation need to be enforced, instead of dancing around a follow up they are asked about a “round up,” must now brand the immigrants whom this affects as the enemy. The must say “illegal immigrants broke the law, so they are criminals.” When a politician’s position is that there must be some exceptions, they must brand immigrants as hard working contributors to American society. The middle ground gets no attention. The practicality and morality of either position in this scenario is based on two different narratives. So, when a proponent of one position talks to the other, they can barely identify with each other’s view.

An individual holding either stated extreme view probably doesn’t see themselves as a hard-liner. They most likely understand the difficulties, impracticality, and moral problems that arise from implementing an absolute stance on an issue. But if political leaders aren’t expected to address the concerns of their own stance, the debate dies. Partisans are left with only one option and that is to win at all costs, because the groundwork for compromise is left without any attention.

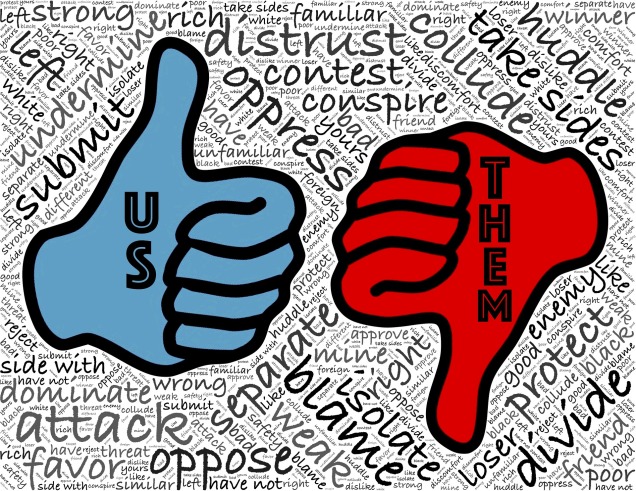

Much of the reason for this condition comes from a constant siege on trust. Watergate, the Vietnam and Iraq wars, politicians convicted of bribery, and the many other scandals and missteps over the years have torn away the idea that our leaders are careful actors of integrity. For good reason, our citizens have lost much of the faith in their leaders and institutions that they had in the early 20th century. Today, this mistrust has permeated down to the cultural and individual levels. Some citizens do not trust our police. Some do not trust certain ethnical groups. Perhaps most problematic, people holding different views on an issue presume the other side to be acting in bad faith.

If someone arrives at an argument assuming the opposing view is founded on bad faith there is no room for middle ground and no room for compromise. Thus the “win at all costs” mindset is strengthened and robust debate dies. This condition is cancerous to our republic and without a remedy we are doomed to fall into the tyranny that Plato forecasted will come of such democracies.

To shift this discourse and serve the public by informing them of the implications of proposed legislation, citizens must reject the paradigm that says the opposition is fundamentally flawed and thus no idea they present can be valid. We must challenge the ideas of our own parties and representatives that we generally agree with. We must understand the negative implications of our own championed policies and leave room for those who dissent. It’s intellectually honest to do so.

It’s been a long road to mistrust and it will be a long road to rebuild it. We must turn around now or accept our fate. We must read. We must hold our politicians to the same standards we expect of our children. Most importantly, we must seek to understand our neighbor and care how they arrive at their views, without making assumptions to suit our own cause. Our founding documents allowed for this. It’s our duty to leave room in each of our American hearts for the people who hold the diverse views that made us the vibrant leader of the free world in the first place.

-Justin Louis Pitcock

Justin is a US Marine Aviator, family man and proud American